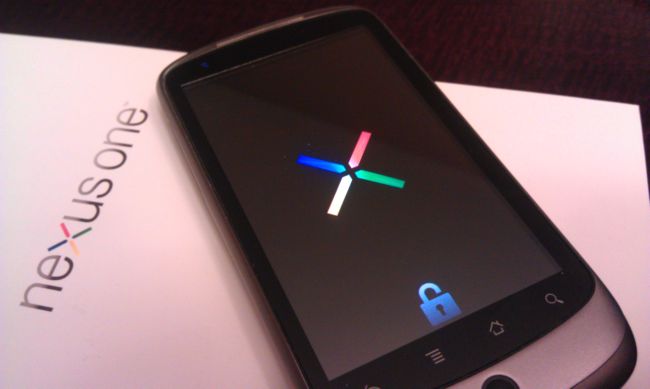

Unlocked and ready to roll.

Unlocked and ready to roll.

Moore’s Law is a popular tech journalism touchstone. It states, roughly, that the raw processing power of electronics will double every two years, and it’s been generally true for the last 45 years. It’s why trying to make a smart computer, tablet, or smartphone purchase these days feels like choosing a car in a Formula One race happening 18 months from now–after alien xenomorphs have arrived on Earth and started working with Ferrari engineers.

There’s a parallel to Moore’s law in how we appreciate bold-for-its-time technology. Call it Szekely’s Principle, derived from this inspired oration.

Try to remember the impact the iPhone had on technology, popular culture, and the future of wireless technology when it arrived. It revolutionized touch-based interfaces, modern phone designs, the nature of mobile data (by means of including a browser that made one actually want to access the web on a phone), location-based services, the cultural significance of a fancy phone, and, soon after, the direction of software development. But these days, we’ve already decided that the next version of the iPhone and its software–already many times more powerful and stable than the first version–is disappointing (if still closely watched). Because, presumably, Apple isn’t adding yet another hardware capacity or brand new, never-thought-of feature.

It’s harder still to think back to when the Nexus One launched and appreciate what it really meant, both at the time and for the future of the Android platform. But allow me to give it a shot.

There were Android phones before the first Nexus, of course, and even Google-blessed “launch” phones. The G1 (code-named HTC Dream) was the first Android phone you could buy, and it looked the part. The myTouch 3G (HTC Magic) brought out Android 1.6, and the first touch-only Android interface. The Motorola Droid (Milestone) was basically the first Android that made some waves, shipping with Android 2.0, a built-in turn-by-turn Navigation app, and, most significantly, at least $1 million in Verizon-backed “Droid Does” advertising.

Then came the Nexus. For a good while, rumors of a “Google Phone” cropped up in overly hopeful headlines, despite steadfast denials. But this was before Google had botched their Buzz social network launch, before too many go-nowhere acquisitions–before it looked like they could falter. It seemed like Google was poised to target the U.S. wireless providers and introduce some overseas-style competition and device freedom. Maybe they’d even go so far as to offer a data-only phone driven by Skype-like VoIP services–after all, they had bid on wireless spectrum, and they needed something drastic to really shake Apple’s confidence in the iPhone, right?

Google employees picked up a Nexus One as a kind of holiday bonus in late 2009, and they couldn’t help but tweet them. It looked like the soothsayers were right–this was Google’s purest vision of what an Android phone could be, hardware and software. Google would sell the phone directly to consumers, with no contract lock-in, for $530, but one could make a case for long-term cost over initial sticker shock. Google was even going to handle software support for the Nexus One, and assured us that this phone would be the first to get software updates. It’s hard to imagine how novel that concept was, even at that early phase of Android–someone handing you an Android phone and actually promising that they’d stay on top of the updates. What’s more, the Nexus One would be the easiest phone to unlock, “root,” and load with a third-party operating system.

When it finally, actually launched, the Nexus One introduced universal voice input, a now common feature on smartphones that’s still under-utilized. Say “Navigate to Target,” and Google, using its best knowledge about where you are and what’s near you, comes back with turn-by-turn directions and time estimates to the nearest big red box. Navigation technically launched with the Motorola Droid, but let’s step back and keep Szekely’s Principle in mind. You are talking to an immensely powerful computer in your hand. That computer takes your voice, turns it into a text command, and beams it in wireless fashion to a giant data center. Meanwhile, that computer and data center are also using space-based satellites and massive Wi-Fi databases to figure out where you are. When it has the request and your location, Google’s thrumming servers then reference that data against extensive maps of the United States, which they acquired by driving camera-topped cars literally everywhere, and returns all that to you, with a computerized voice to read each step as you approach. But then your phone suggests you take a left onto a street closed that morning for construction, and you get really mad at it.

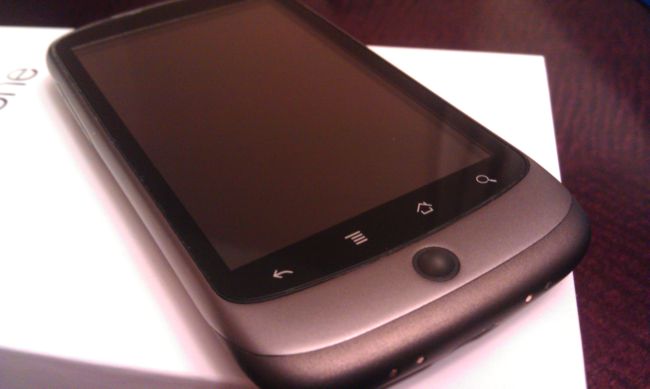

Just as important, the Nexus One was the first direct approach at the iPhone–shape, feel, and a good bit of the function. The Nexus One certainly looked the part, being the flattest, sleekest Android to date, with just one physical button on its front and simple branding on the back. It was also the first phone to include iPhone-style multi-touch gestures. The players and dates change in different tellings, but the basic story is that Google kept “Pinch to zoom” finger actions out of Android to appease the CEO of then-friendly rival Apple; eventually, though, Google’s CEO left Apple’s own board, and the niceties ended (and the lawsuits began).

After the initial buzz, though, the Nexus One proved to be an earnest failure, at least as an actual product. Sales didn’t exactly sing, the forum-and-search-based support didn’t win much praise, and, as tends to happen, the limitations made themselves known: limited room for apps in the internal memory, somewhat mediocre-to-okay camera and speakerphone performance, and (initially) a dependence on T-Mobile’s 3G network, which remains a solid fourth place contender in the U.S. Google made a point of pointing to future Nexus One releases through Verizon, Sprint, and AT&T, but only AT&T materialized. And, to say the least, the Nexus One didn’t change the way phones are sold and connected in the U.S.

Me? I loved my Nexus One. Best device I’ve bought in my life. Part of that is how I bought it: off-contract, with a cheap T-Mobile data plan already in place (for my contract-price G1), enthused about using it to write an up-to-date Complete Android Guide. It felt just fine in my pocket, it didn’t need a case, and while the camera wasn’t amazing, it was the camera I always had with me, as evidenced by my (kinda neglected) Flickr stream. The Nexus One was indeed the first phone to get the Android 2.2 update, and since it’s the phone of choice for Android developers, I’ve basically never had a compatibility issue with a Market app or third-party firmware. But then the Nexus S launched, and ol’ model One took a good long while to get its Android 2.3 fix, behind the new Senior Prom King Nexus.

I sold my Nexus One recently, mostly because I changed cellular carriers, and mailed it out yesterday. The HTC Thunderbolt isn’t a bad trade-up, but it lacks the bravado of the N1. The first release from Google’s Nexus project shows that an Android phone could be sleek, unashamed of its iPhone aspirations, and still delightfully geeky deep in its guts. It was a benchmark for almost all Android phones that followed, and, forgive the overused analogy, but like “The Velvet Underground & Nico,” it might have sold only a few thousand, but almost everyone it sold to became an even more devoted Android fan.

Lately, of course, when people have asked to see my former phone, they wonder where the front-facing camera was. Or why it doesn’t have Instagram.