Photo by dennis.tang.

Photo by dennis.tang.

I’ve become something of a coffee snob lately. The snobbery took root in research for a Lifehacker feature, then quickly grew to encompass two kitchen cabinet shelves, quite a few spare thoughts, and whatever discretionary dollars I can justify. It’s at the point where, standing outside myself, I can see what it looks like to make a pained decision between single estate Colombian and triple African Kona blends. The word “precious” comes to mind, but here’s how I can forgive myself.

Warning: This post has a larger point than coffee. But it does contain a lot of coffee nerdery. So it’s both pretentious and presumptive, and possibly a piece of professional procrastination. You’ve been warned. If you don’t want to second-guess your own coffee setup, I recommend skipping to the part where I try to make an analogy out of a hand-cranked Japanese thingamajig, and also switch into the second person, as just happened earlier in this warning.

Whether you’re making espresso or drip-based coffee, you have control over certain factors: the quality of your beans, the ratio of coffee solids (beans) to water, the way in which you’re grinding and exposing those beans to water, the temperature of the water, the length of time the bean grounds and water interact, and how you extract the water from those grounds. Each of these facets has many smaller facets: “quality” means the origin, age, roasting, and storage of your beans, for example. Every coffee system has its trade-offs between control and convenience. Using a Keurig system, for example, surrenders control of basically every part of the process, save the basic choosing of a box of plastic K-cups, in exchange for a one-button cup of coffee. On the other end, you can own a coffee plantation, invest heavily in roasting equipment, and keep only the most finely tuned brewing and heating instruments on hand. Somewhere in the middle lies most of the coffee you will really, actually enjoy.

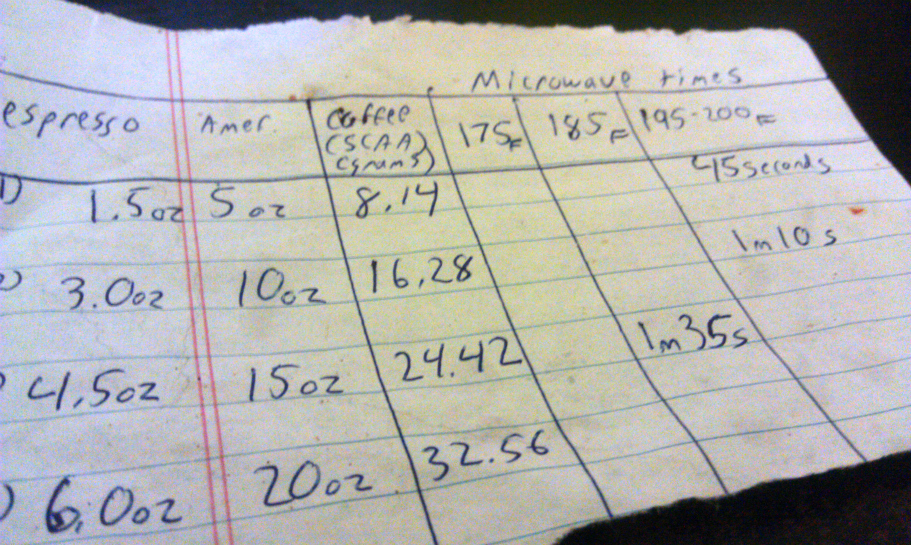

My preference is the inverted Aeropress method, which is something like a hybrid of a French press and hand-powered espresso machine. To get better coffee from the system, I’ve run some experiments and taken some notes. For each amount of coffee I want to make–every 1.5-ounce espresso-like “shot,” or every five ounces of espresso-plus-water “Americano” coffee–I’ve measured out the coffee-to-water ratio set down by the Specialty Coffee Association of America, along with the timing on my particular microwave to get that amount of water to a certain temperature.

Knowing all that, the only thing left is to get some coffee grounds ready. The AeroPress is like a syringe, creating a vacuum seal that you press liquid through with your hand power. If you grind your coffee too finely, a la espresso, the grounds can create a seal and cause you some serious anguish and embarrassment, as even the most dedicated gym rat will look ridiculous trying to out-muscle the universe. Grind too coarse, closer to French press styles or the pre-ground supermarket stuff, and your water doesn’t get optimum exposure to enough surfaces of your beans. So you aim to get a consistent grind that’s just in the right in-between spot, and that is best accomplished with a burr grinder, not an electric-powered blade.

So most every night, or sometimes early in the morning, it’s time to pull Hario hand grinder off its shelf, grab an airtight container of beans, and get down to it. To adjust the fineness of the grind, you must manually open or close the opening between a ceramic cone and its sheath by tweaking its central screw. With experience, you can generally eyeball the pieces and know what will come out between them. You load beans into the top, but not so many that you’ll spill them while you’re grinding. Then you start grinding.

At first, nothing is happening. You hear something and feel the resistance shiver up your arms, and if you lowered your eyes and looked into the reservoir, you’d see that there was, indeed, grounds starting to pile up. But you look at the beans, and despite how your arm starts to feel after a few dozen turns, it looks like the beans haven’t moved at all. You think about the electric grinder, which is more like a chopper, but at least you see the beans fling themselves about in its lid and get smaller with each pass, and all you have to do is stand there and keep the button pressed down. Still–keep grinding. If you must, take a break and look at what you’re turning out. It’s consistent, it looks really nice, and you’re the one who created it. Now–back to the grind.

Photo via Gimme! Coffee.

Photo via Gimme! Coffee.

Eventually, you notice the level of beans has indeed lowered, and soon after that, you’re just grinding in a state of contentment. If you’re alone, you might even be able, to paraphrase The Miracle of Mindfulness, to grind the coffee not just to ensure good coffee the next day and get back to your evening, but to grind the coffee in order to grind the coffee. You’re investing in a better product, giving your arms a workout, and cementing in your mind the real cost of good things. But all you know is the crank, the container, and the sound and vibration of the job. And then you’re done.

My wife has yet to say my grinding habit is ridiculous in so many words, but I catch that feeling. We don’t have shades or curtains on our kitchen windows yet, so the neighbors might think my late-night hand-cranking sessions are–well, let’s just hope for the best there. But I’m going to keep doing it. Having left my pre-defined job at Lifehacker for a more pick-and-choose freelance writing gig, and now trying to pick up some web and coding skills despite the seeming enormity of the field, I like to think my tiny hand grinder is teaching me big lessons. About dedication and quality, sure. But also about when it’s time to simply work at something, forget what you “look like,” and take good notes on what you’ve learned.

Like I’m trying to do here.